By DANA TIMS/Lincoln Chronicle

Thousands of gray whales now migrating north from Baja California are in such poor shape and so few calves were born this winter that researchers and others worry they may be witnessing another die-off.

Researchers believe their poor condition is due to changing feeding conditions in the Arctic, which could mean the whales were already in poor shape last fall when they began their 12,000-mile migration to breeding and calving grounds off the coast of Mexico.

Now, early reports of their northern return are uniformly dismal.

At least 80 gray whales died this year in Baja’s protected lagoons, where wintering females give birth to their calves and single adults look to mate. Volunteers on the California coast counting whales migrating north are reporting emaciated whales with record-low numbers of calves.

Alisa Schulman-Janiger leads an effort just north of Los Angeles to count Pacific gray whales migrating north past Oregon toward summer feeding grounds in the Bering Sea.

This year, more than any other since Schulman-Janiger began heading the census in 1979, she’s not liking what she sees.

“The numbers so far are the lowest ever and the whales we are seeing are extremely emaciated,” she told the Lincoln Chronicle. “They have bulging ribs with shoulder blades and vertebrae visible even from shore. It’s really just horrific.”

Mothers with calves are nearly non-existent, she said, indicating the mothers are likely too unhealthy to birth and feed healthy babies.

During last fall’s southbound migration, Schulman-Janiger said, not a single calf was spotted, a phenomenon never before reported in the 40-year history of the group’s census.

Fewer numbers of whales showed up this winter in the relatively remote lagoons along the coast of Mexico, likely meaning they had to travel farther south than normal to find food and the warmer water they prefer. That longer commute, in turn, translates directly to burning far more calories than during past migrations.

“The distribution this year is far more extreme than what we have seen in the past,” said Jorge Urban, head of the Marine Mammal Research Program at the University of Baja California Sur. “There is a lot more work to do for us to really understand what’s going on, but everything we are seeing right now is very sad.”

A warming Arctic

Josh Stewart, an ecologist in Oregon State University’s Marine Mammal Institute in Newport, traces the dangers facing gray whales directly to a massive Arctic warming trend that left many malnourished.

“All the signs are indicating there has been a pretty intensive change in the Arctic,” he said. “It’s one of the most rapidly warming places on the planet and what we’re seeing now are the impacts of climate change in real time.”

That warming is a concern because it’s causing sea ice to melt faster and farther than usual.

In prior years, longer-lasting sea ice gives a type of algae on the underside of the ice time to fully mature. Once fully developed, the algae die and sink to the sea floor where, under normal conditions, their numbers are sufficient to essentially fertilize the sea floor. That triggers the growth of the shrimp-like creatures that gray whales prefer.

“Now, less dying algae is making its way to the sea floor,” Stewart said. “Instead, it’s getting mixed into the water column, causing a huge shift in the amount of available biomass.”

Stewart and other researchers are quick to note that this is not the first time gray whales have experienced significant declines in numbers and overall health.

They were hunted nearly to extinction in the mid-1800s and again in the early 1900s for their blubber, which was used mainly as fuel to burn oil lamps.

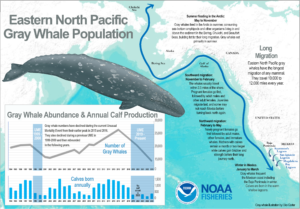

In 2016, NOAA researchers estimated the gray whale population at 27,000, declining to below 15,000 in 2023 before rebounding to a rough estimate of 19,000 in 2024.

NOAA declared an official Pacific gray whale “unusual mortality event” in December 2018. It wasn’t lifted until November 2023, with peak whale strandings occurring over a two-year period starting in December 2018. During that span there were a total of 690 gray whale strandings, with 347 in the United States, 316 in Mexico and 27 in Canada.

An investigating team concluded that localized ecosystem changes, including both access to and quality of prey, caused widespread malnutrition that led directly to struggling whales washing up on West Coast beaches.

The number of whales counted so far this season illustrate just how far the population appears to have dropped compared to just one year ago, according to Schulman-Janiger’s census work in California.

In 2024, for instance, volunteers counted 224 gray whales traveling south and then 544 traveling north with 21 calves. During the southbound count this season, only 124 whales were tallied. The northbound count, with six weeks left, has plummeted to 419 whales, with only three calves observed.

“This year’s count makes last year’s look like a lot,” she said. “And last year was terrible.”

Survival strategies

Stewart and others acknowledge the obvious effects that a reduced food supply has on gray whales. But they also point out that grays, as opposed to krill-reliant blue whales, have an ability to change their foraging techniques. They can also feed on as many as 90 other species, including surface-dwelling krill, eel grass in the mid-waters and bottom-skittering crab larvae.

“Gray whales have lived through huge periods of climate change in the past, from ice ages to more recent warming events,” Stewart said. “They are very adaptable. I don’t think they’ll go extinct, but their numbers have certainly dropped significantly in the past and they might again as the current number of gray whales will have to compete for diminishing food resources.”

Knowing that thousands of gray whales are once again headed north past Oregon, researchers will be watching closely to see how many strandings will be reported in coming months.

“There have already been strandings reported in Baja and elsewhere in California,” said Jim Rice, who coordinates the Newport-based Oregon Marine Mammal Stranding Network. “We know there are likely to be strandings here, as well, but hopefully not in record numbers.”

In an average year between three and six gray whales end up stranded on Oregon’s beaches, he said.

“A dozen or more would be quite a large number,” Rice added. “Really, anything over 10 would be exceptional.”

Off the California coast, where Schulman-Janiger and her team are charting the migration, grays are just making their way past them heading north. During one recent session, Schulman-Janiger initially thought she was viewing a mother and calf. Upon closer inspection it turned out that the “calf” was a rib so unprotected by blubber that it was bulging far away from the whale’s body.

“We have six more weeks to finish the northbound count and I hope to see a lot of whales,” she said. “I hope to see a lot of calves, but that doesn’t seem likely. There haven’t been many strandings here yet, but I don’t see how the whales I saw today are ever going to survive to Alaska.”

- Dana Tims is an Oregon freelance writer who contributes regularly to Lincoln Chronicle and can be reached at DanaTims24@gmail.com