By SHAYLA ESCUDERO/Lincoln Chronicle

SILETZ – Twenty-three graduates at Siletz Valley Schools received their diplomas in the hot Saturday sun, some adorned with eagle feathers, beads and cedar-woven graduation caps.

While the joyous day was filled with school pride and honor songs, the celebration did not ignore the turmoil in leadership its students endured the last four years and even in the last weeks of their senior year.

Facing a budget deficit, staff layoffs and mounting complaints, the Siletz Valley Schools’ superintendent/principal stepped down and placed on administrative leave last month – a sucker punch delivered at the end of the school year.

With little communication from the charter school’s board, students, staff and community are left scrambling – there is no certainty of how many staff have been cut, the changes to classrooms, how big the budget deficit is, or exactly why the school lost its second superintendent/principal in two years.

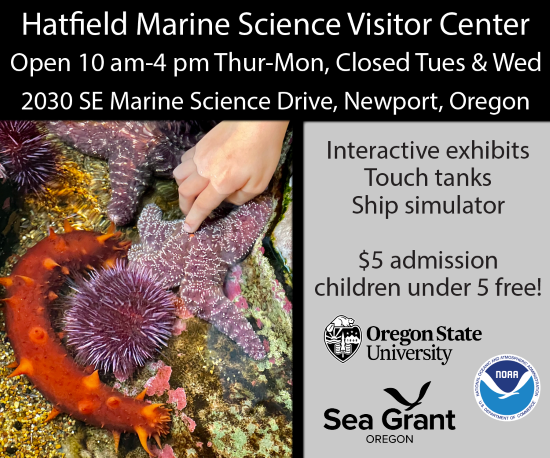

Siletz Valley Schools sits at the heart of the 1,200-person town, encircled by the river of the same name. Founded in 2003, after the Lincoln County School District closed the school, the charter operates independently with its own board and budget – primarily funded from state and federal money and tribal grants. The majority of the K-12 school’s 223 students are members of the Confederated Tribes of Siletz Indians.

Over a year ago, the school made headlines when the former superintendent was fired for her treatment of students who protested when the school did not observe Indigenous Peoples Day as a holiday.

Now, the school is grappling with a host of other issues. Declining enrollment, shrinking federal grants and a misstep in applying for a $176,000 tribal grant for sports created a deficit the school board chose to balance with layoffs, combining classroom subjects, forgoing updates to the school’s building and slashing a prospective program.

In the last weeks of the school year, the superintendent/principal stepped down the same week students protested the loss of a beloved teacher.

The board sees the change in leadership as a way to address the concerns of the school and how it can build trust again. Staff say students, staff and the tribal community need to be involved in decision making – including the hiring of a superintendent to prevent a repeating pattern.

Layoffs

Social studies teacher Richard Canales likes to connect his students with history that helps them learn more about themselves. With a predominantly indigenous student population, that means researching the local history of the Siletz Tribes and connecting with real world issues.

“I want them to discover more about themselves … That’s the kind of stuff that engages them,” Canales said. “And even to students who aren’t tribal members it’s important for them to know about the people in their community.”

Canales taught at the school for four years, mostly teaching high school grades.

Because of the budget cuts, Canales wasn’t completely surprised when he was told in late May that his contract would not be renewed. He knew the charter school was in a tight spot financially – he attended school board meetings regularly and went to the first budget meeting where the board proposed decreasing health benefits to make up for the financial shortfall.

But he didn’t think things were so dire that his position would be on the chopping block – especially because social studies is a core subject.

Word travels fast in the community. By the next week, students took to protesting, chanting in the halls and walking out of class, carrying signs that read “We love Canales” and “Save our education, not your money.”

Community members voiced their opposition to Canales’ layoff during a May 27 board meeting. Some parents and students said Canales was the only teacher that students went to school for or who understood them.

The board did not address their concerns during the meeting, according to the recording on the school’s website.

In the days that followed, attendance declined. It always drops off towards the end of the year, Canales says, but this year there were even less students.

“It’s gloomy, students aren’t showing up, they are legitimately angry,” Canales said.

And frustration in the community mounted without many answers.

The proposed budget is not on the school’s website, and there is no way of knowing exactly how many positions were eliminated or how big the deficit is. The school is also inconsistent with uploading meeting recordings and meeting minutes on their website.

Stepping down

That same week, Ginger Redlinger stepped down as the superintendent/principal – the same day multiple staff penned complaints.

In the last six weeks leading to her departure, there were five complaints alleging dereliction of duties and lack of communication. A May 20 complaint was critical of her misstep in applying for the tribal grant.

“More recently, outreach to the Confederated Tribes of Siletz Indians Tribal Council for financial assistance is troubling for many reasons,” one complaint read. “First and foremost, it puts a strain on a vital relationship between the school and the Tribe. Secondly, it is a particularly risky situation given the dire circumstances regarding our school budget.”

The complainants recommended the principal and superintendent role be separated to better fulfill all their responsibilities and a petition circulated the school demanding Redlinger resign.

The board accepted her resignation during a special meeting May 22. She continued to work in the building until the board placed on administrative leave June 3. Student adviser Debra Barnes was selected as the interim superintendent during the June 3 meeting.

It’s true that Redlinger didn’t apply for the grant, board chair Willie Worman told the Lincoln Chronicle and the board was informed of that about two months before the staff complaint. At a previous board meeting, records of which are not publicly available, the superintendent assigned blame to herself and the tribe for not securing the grant.

“We have a whole council with multiple tribal members that are involved in some of those meetings … so it was clear this was absolutely a school issue and not a tribe issue,” Worman said.

He said Redlinger then went before the Tribe to “humble herself” and ask for the funds, again.

“Somewhere in the midst of that, the funds still weren’t requested,” Worman said.

The Tribe along with the staff that manages its charitable contributions fund did not have any information to provide the Lincoln Chronicle, according to a tribal spokesperson.

Redlinger did not respond to requests for comment, but in a parting message to the school community she informed staff she had submitted her resignation.

“Wind blowing, umbrella up, and away I go! I am off to my next adventure – well I will be after June 30 – and it has been an absolute joy to work for this community,” her email said.

For some members of the school community, the turmoil of the last weeks of the school year felt familiar. Superintendent Casey Jackson was fired December 2023 after shaming students who walked out of class in protest on Indigenous People’s Day.

Now, almost two years later, the school had lost its superintendent in what some saw as a strain in the school’s relationship with the Tribe. And again, students were trying to have their voices heard – protesting the layoff of Canales.

Staff formed a union after the incident with Jackson, said Canales, who is technically the union head. The group is part of a chapter but hasn’t yet secured a contract with the school.

He believes the issues in communication and leadership aren’t solely on the superintendent but also the school board. Staff felt they were not being heard because there were complaints against Jackson before the Indigenous People’s Day incident, Canales said, and before she was even hired as a superintendent.

“The school has a lot of work to do to build trust with the community,” he said.

Communication

As the school year winds down, staff and students still aren’t clear which classes will be restructured and how teaching will be affected. Without consistent meeting recordings, meeting minutes, agenda packets or a publicly available budget document, there aren’t many places to find answers.

On the school website, there are two board meeting recordings from May 21 and May 27. Before that the most recent meetings date back to February despite the board holding regular meetings every month. It is unclear which meetings discuss the budget and without consistent online notices it is not clear how many times the board met to discuss the budget or other issues.

Worman acknowledged that notices of board meetings haven’t consistently met Oregon’s public meetings requirements, and the school doesn’t have a quality website. But he hoped a new superintendent would ease some of the frustrations around communication.

“It’s up to us now to hire a very strong, high quality, superintendent and get someone in this building that’s going to believe in communication and transparency, building trust and absolute accountability,” he said.

Money issues

The 2025-26 fiscal year’s budget may have been one of the most difficult in the school’s history to try and balance, Worman told The Chronicle.

While a sparse official budget document has statements about reductions in revenue, it is not clear how large the shortfall is or what actions were taken to fill the gaps.

The $5.3 million budget has shrinking revenue sources. The school expects to get 25 percent less federal funding from Title I funds designated for schools that have lower income students. Most school funding from the state is calculated using enrollment, so as the school loses students it also loses money – an issue throughout Oregon.

This school year, Siletz started with 235 enrolled students. Over the course of the year, the school lost more than 10 of them.

“When we are going through struggles like, four superintendents in five years, declining sports programs, and having to cut some programs and combine classes, this only aids in the desire of folks not wanting to keep their kids in their hometown school,” Worman said.

The school missed an expected $176,000 grant from the Siletz Tribe because Redlinger did not secure the funds, he said.

That grant was meant to cover the cost of sports this school year. Worman said the board was told the money was coming and that the funds from Tribe’s Charitable Contributions Fund are given on a reimbursement basis. So the school was spending money out of its own coffers to fund athletic programs, he said.

The board forecasted in February the district could have a budget deficit for 2025-26 and relayed that at an all-staff meeting. But board members didn’t know then the extent of the issue or how they were going to balance the budget – a process that comes in the spring.

In one earlier budget committee meeting, it considered decreasing health benefits, but after receiving feedback from staff, changed that approach.

To balance the 2025-26 budget, at least four positions were eliminated, classroom subjects combined, curriculum not updated, building maintenance put off, and cut a prospective program aimed to help vulnerable students.

When deciding how to decrease employee expenses, Worman said the school board evaluated which teachers could teach more than one subject so that classes could be combined to make up for eliminated positions.

But staff were not warned of the potential changes before the decision was made.

In the end, a full-time teacher and two instructional assistants were cut with some staff expected to teach combined subjects – such as math with science and social studies with humanities. The vice principal position was eliminated and that staff member will teach combined subjects. It is likely an office worker’s position will also be cut, but at the end of the school year which position was not decided yet, Worman said.

But even with those reductions, there are still other ways the school needs to make up for the losses.

“We also had a fairly broad building maintenance plan that we’ve had to reduce by almost nothing,” Worman said. The school dashed plans to rebuild their grandstands as well as needed building upgrades.

The board also had to cut a $273,000 program slated to launch in the fall to give extra support to students in danger of not graduating. Worman said the board hopes to proceed with the program if finances improve.

The public charter school is separate from the Lincoln County School District with its own board and budget.

The charter reports its budget to the school district because money from the state is first handed to the district before making its way to the charter. So the district often communicates with Siletz about deadlines, said LCSD Superintendent Majalise Tolan.

In 2023, the district didn’t provide any oversight because it could be used to review complaints against the school, Tolan said. But she still sent staff to keep an eye on what was happening and to show support.

Moving forward

On Saturday, Siletz High School’s graduation began with a drum circle.

The 23 graduating seniors watched – clad in red robes, some with eagle feathers and beadwork along their graduation caps. Canales kneeled and crouched to take photos of students as they received their diplomas, handed roses to their loved ones and listened to commencement speakers.

It was not lost on speakers or the students that the graduating class of 2025 had seen a heavy turnover in leadership – in their four years there were five people who took up the official or interim superintendent role.

Speakers read messages from graduating seniors, thanking their teachers and recounting moments during their school years that impacted them. Several highlighted the walkout 1½ years ago and using their voices to protest.

Thersea Smith, who has been at the school eight years and teaches tribal language and culture, watched her son sing in a drum circle. She was also watching students who led the 2023 walkout – an idea that started in her classroom.

Smith is the only teacher who is a tribal member and feels uncertain going into the fall. There hasn’t been communication about the changes teachers may see and she only knows who has been laid off because the teachers have talked with each other. Smith knows she has a contract for 2025-26 but doesn’t know what subjects may be combined for her, or what other teachers will be teaching.

Smith believes tribal voices, parents and the larger community need to be included in the choosing of the superintendent/principal. She hopes the process won’t be rushed to find the right people for the job.

For the first time, students helped shape Saturday’s graduation ceremony, Smith said. That, she believes, represented a coming together between tribal members, the school board, students, parents and the community – a beautiful representation of what the school could be.

“I choose to teach in Siletz because these kids are the future of the Tribe,” Smith said. “If we don’t do anything this could be another example of how the public school system failed Native kids. We need to do better by these kids.”

- Shayla Escudero covers Lincoln County government, education, Newport, housing and social services for Lincoln Chronicle and can be reached at Shayla@LincolnChronicle.org

Why did the Lincoln County School District close this school years ago? Why isn’t it part of the school district? With the number of students it has that sure seems like it should be part of the district.