By SHAYLA ESCUDERO/Lincoln Chronicle

Waldport High School assistant principal Steve Cooper broke news to the girls volleyball team at the beginning of practice – the cell phone policy will be changing beginning this week. Immediately questions began to unfurl as the team sat across the gym bleachers.

Students were used to having cell phone restrictions, so what did a statewide order from Gov. Tina Kotek mean for them?

The start of a new school year marks another step in the crackdown of cell phones in public schools – and a slight change for most Lincoln County School District students. Now, there will be no cell phones, smart watches or personal electronic devices the entire school day, including between classes and at lunch.

Under Kotek’s order, every school district in Oregon will have to adopt a policy prohibiting student cell phone use by January. The Lincoln County district already adopted its cell phone restrictions, with some variations across schools.

With the new blanket policy, some teachers let out a sigh of relief as the changes lift some of their enforcement responsibility.

But the biggest change at most schools of not being able to use cell phones during lunch or between classes is generating mixed reactions from students.

The policy and practice

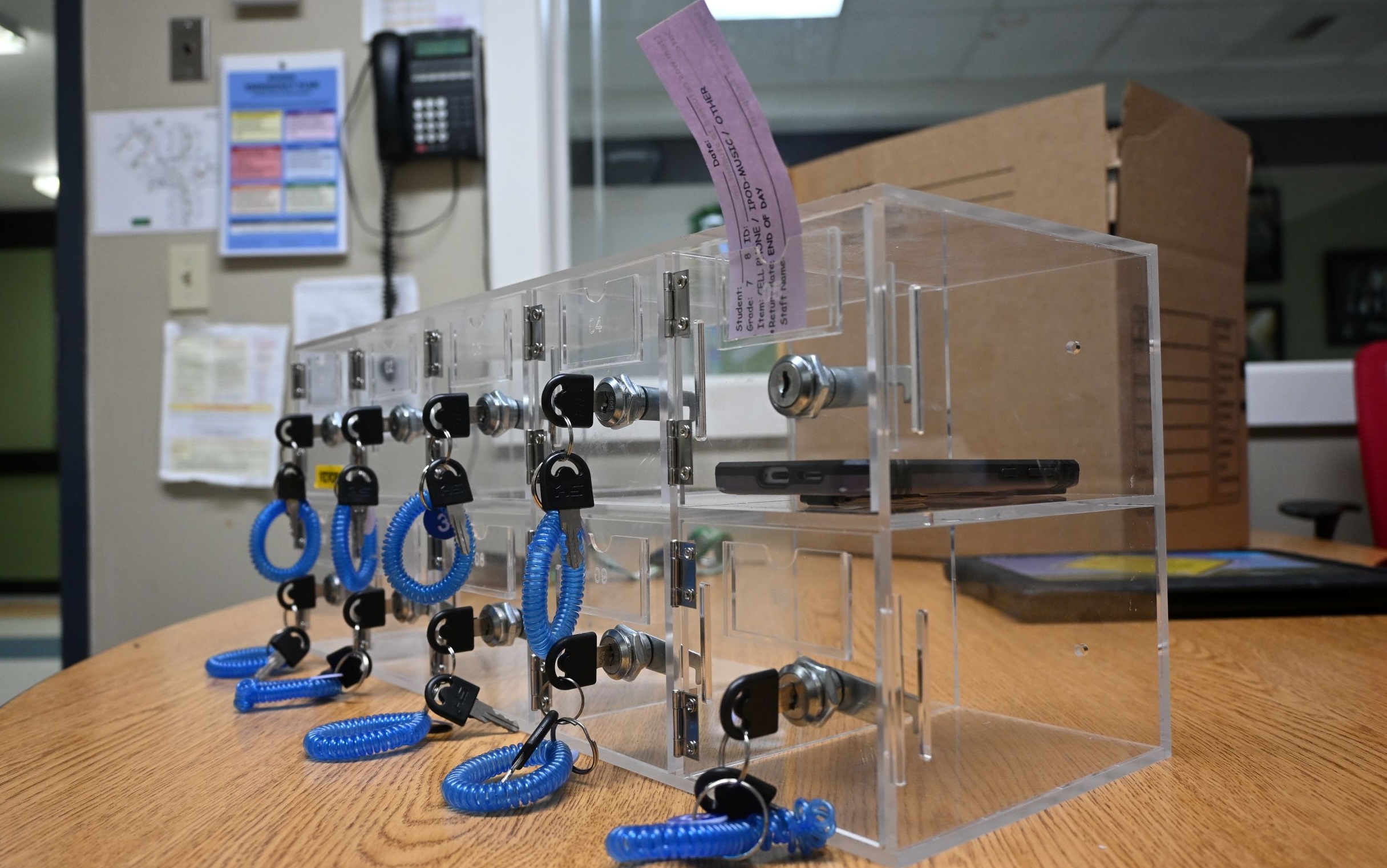

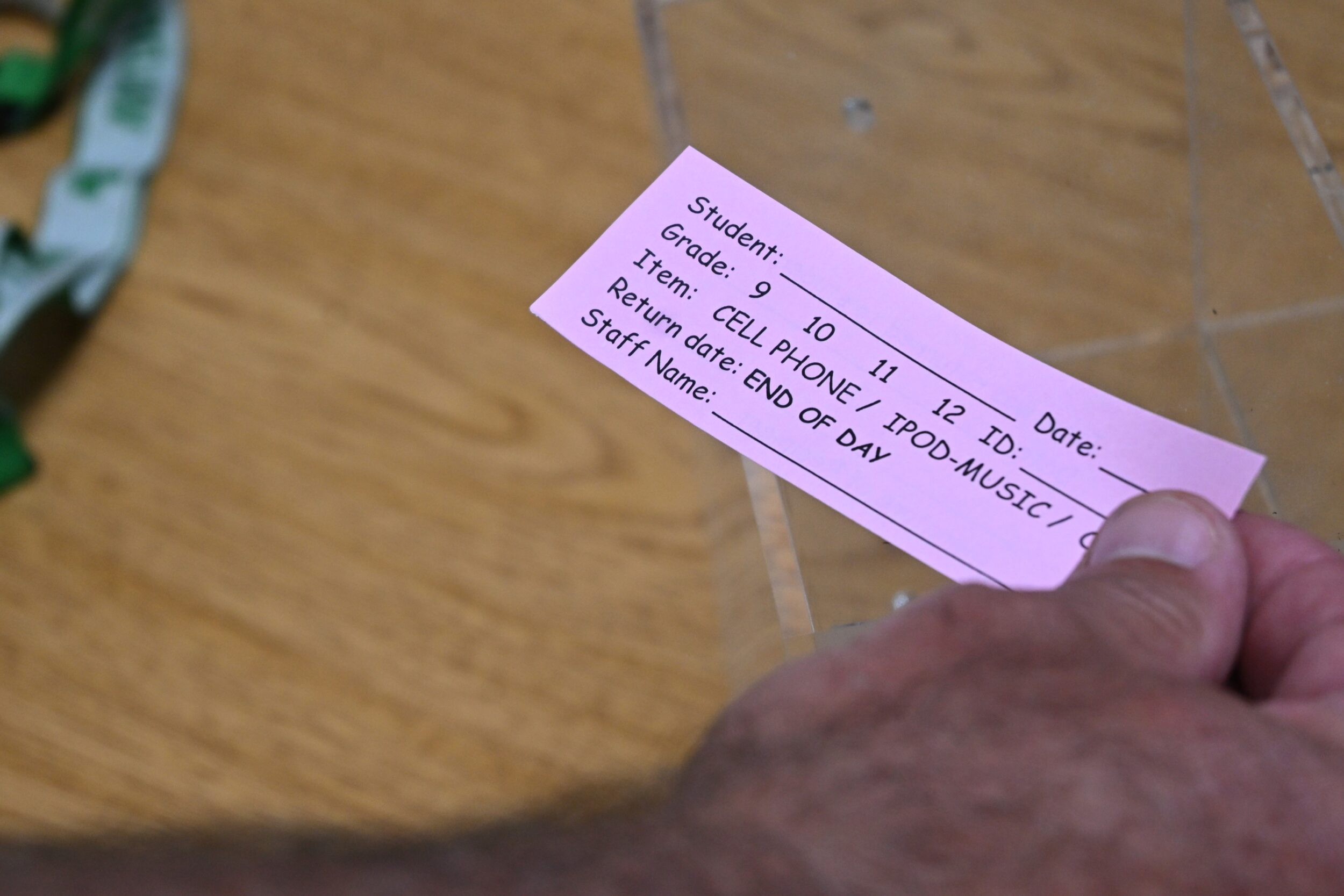

Cooper winds a key to open the transparent door of the plastic 10-cell block students call the “cell phone jail.” At the top is a pink slip used to identify whose phone is in the cell, its twin copy meant to show the teacher that the student turned their phone in. Then the teacher updates a shared form that keeps track of student violations.

It’s a system Cooper designed.

Students receive a ticket if they are caught with their phone and are instructed to take their device to the cell phone locker. On their first offense, students get their phone back at the end of the day. On the second, their parents must retrieve it. And on the third, the student has to check their phone in the cell phone locker every day for a week. Any future offenses result in a major referral where the students, parent and an administrator meet in a conference.

Students are given a clean slate every nine weeks, and few students make it to the third offense. The system worked well for Waldport high and middle schools last year, Cooper said. As time went on last year, he said, there were fewer cell phone violations.

Part of the rollout had to do with messaging from staff, making students aware why the policy was in place and education around cell phone use.

“We talk a lot about mental health and cell phone use with our students and how it affects their sleep patterns,” he said.

Getting parents on the same page was also an adjustment, Cooper said, since many of the calls and messages students were receiving were coming from their parents. In an emergency, the main office should be used to contact parents and there are approved exceptions to the policy when involving accommodations and translation.

While all LCSD schools have a cell phone policy, each one looks a little different.

At Taft Middle/High School in Lincoln City, cell phone use was banned in 2023 during the whole day. Students bringing their phones to school have to put them away in special magnetically locked Yondr pouches.

Now, all of the district’s schools will have a “bell-to-bell” policy. But how that plays out in each school building may look slightly different.

Governor made changes

Kotek signed the executive order in July prohibiting student cell phone use during the school day at all of Oregon’s public k-12 schools. The order was signed after House Bill 2251 which would have banned cell phones from the start of the school day to the end, failed to pass the 2025 Legislature.

Proponents of the bill argued that cell phones distracted students and contributed to mental health and bullying issues. Some school district leaders opposed the bill, in favor of leaving the decision-making authority up to individual districts – many who felt they didn’t have the resources to enforce.

Kotek’s executive order means that every Oregon school district will have to adopt a policy prohibiting student cell phone use by Oct. 31 and policies must be in full effect by Jan. 1, 2026.

“For LCSD schools, the governor’s order will not represent a major shift,” said Aaron Belloni, LCSD’s deputy superintendent of student services.

Each school will follow district policy while tailoring their approach to fit their specific building and may have slightly different responses to policy violations, Belloni said. For example, some schools like Taft may use Yondr pouches while others like Waldport will expect students to keep the devices in their backpacks.

The main change will be the extension of the policy during lunch and passing periods, and for LCSD the shift begins with the start of the new school year on Tuesday, Belloni said.

Teachers are largely happy about the legislation, and there is a lot of excitement, especially for other schools in Oregon which don’t have a policy, said Trevor Stewart, vice president of the Lincoln County Education Association and a special education teacher at Newport High School.

“I think Lincoln County was already in a good position when this cell phone policy came out,” Stewart said. “Other schools may not be as ready.”

Teachers can see how cell phones are robbing students’ attention, making it difficult for them to learn, said Janice Venture, the union’s president and a middle school science teacher at Toledo Junior/Senior High School.

“It’s not that big of a change for LCSD but it is a relief to some of us,” Venture said. “The onus isn’t on us; all the hard part is off the teachers.”

At Toledo last year, teachers would confiscate the cell phone on the first offense. Only after the first offense was the school office involved, Venture said. Now, the blanket policy makes it so the office handles the cell phone confiscation completely.

Gray areas made it difficult to consistently enforce the policy, said Toledo principal Chloe Minch. There may have been different levels of leniency because students sometimes want to use their phones to take a photo for a class assignment. But the executive order is clear in what is allowed – it’s no sight or sound and “bell to bell.” It gets rid of the wiggle room, she said.

Now, as the policy changes to include restrictions during lunch time and passing period, Minch believes it’s an effort that involves the whole community’s support, including parents, to understand the rules.

As school begins, LCSD schools have notified parents and teachers preparing them for changes as students head back to the classroom and relaying the details of their individual policies.

Students react

When Waldport’s policy rolled out last year, Alexis MacFarlane was the first student to have her phone confiscated. It was no surprise, MacFarlane said. Even her mother called Cooper to applaud the policy and let him know her daughter would likely be the first to have a violation.

“She thought it was pretty genius that we weren’t going to be allowed to be on our phones as much,” MacFarlane said with a laugh.

She believes she wasn’t only the first person to be caught on her phone but likely had the most violations. Because the policy is no sight or sound, a few of those times her phone fell out of her bag or she would accidentally leave her ringer on, MacFarlane said. But it was hard to not want to look at her phone at the notifications she was getting or if her family needed to get in touch with her.

“I agree that we shouldn’t be on our cell phones during class but not having it in the hallways or lunch is kind of stretching it because that period is our time,” MacFarlane said.

MacFarlane worries about what the change will mean for less outgoing students who aren’t using breaks to socialize and predicts that more students will end up spending more time in the restrooms on their phones to get around the policy.

When Waldport High School placed a restrictive policy on cellphone use, sophomore Bella Saharek noticed a change in how she was learning in class. She was less distracted and having her phone in her bag instead of on her desk lessened the temptation to look at it. She spoke more to her friends, too, she said.

While Saharek liked using her phone during lunch, she sees it as just another adjustment students will be able to make, like when the restrictive policy first rolled out.

“I’m a little bummed,” Saharek said. “But I think it will be fine.”

- Shayla Escudero covers Lincoln County government, education, Newport, housing and social services for Lincoln Chronicle and can be reached at Shayla@LincolnChronicle.org

so leave it in locker say you didn’t bring it? what next locker searches?

I don’t like this policy at all and believe they are using it to keep parents unaware of what is going on in our public schools. My child has a phone for a reason and that reason is so she can contact me at any time for anything. I