By GARRET JAROS / Lincoln Chronicle

NEWPORT – Sunrise is still a suggestion when dawn escorts the two men to jail. Jail is hard, the men will tell you, make no mistake about it. You have to have the right mindset going in, you have to be resilient and you need a support system to help get through it.

Tattoos run down a forearm of one of the men. The death of a close friend from a drug overdose played a pivotal role in his landing in jail. The other man grew up with family members who were addicted to drugs and had criminal histories.

The men have served a combined 31 years in jail and federal prisons prior to that for one of them. And yet both men say they do not mind the time spent behind locked doors. In fact, Lincoln County Sheriff’s corrections officers Lt. Josh McDowall and Sgt. Justin Stark consider it a calling.

McDowall and Stark work 12-hour shifts – with four days on followed by three off and then three days on and four off – at the Lincoln County Jail. And then there is the inescapable overtime.

“The job is hard,” said McDowall, who manages the jail. “It’s not for everybody. The reality of it is if you want a job that has purpose, that has good benefits, and you want to do something where you can lay your head at the end of the night and know you did something positive for the community, this is the place to do it. It’s a place that values integrity. And we hire for character.”

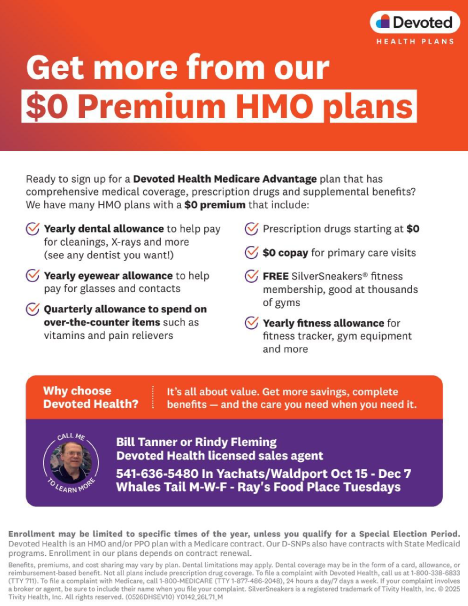

The sheriff’s office is hosting a hiring event from 10:30 a.m. to 4 p.m. Saturday to fill vacancies in the jail, on patrol and in animal care. They will also build a list of qualified applicants for upcoming patrol vacancies. The pay for corrections and patrol deputies ranges from $33 to $44 an hour. Pay for corrections health nurses, of which there is an ongoing shortage, range from $44 to $56 an hour.

A complete list of jobs and salaries is posted on the Lincoln County career page. The hiring event will be held at the sheriff’s Search and Rescue building, 830 N.E. Seventh St., Newport. Participants are encouraged to sign up prior to the event and can visit the sheriff’s office website for details.

Answering the call

McDowall, a Toledo High School graduate, said a career in law enforcement never crossed his mind until it was suggested to him while he was working at a cell phone store in Newport — a filler job while he healed from a construction accident.

He had worked a variety of jobs after high school, tried college but found it “was not my cup of tea.” He planned to return to construction when the store’s manager introduced him to her boyfriend, a Toledo police officer. Another store employee was in the sheriff office’s reserve program.

“They saw something in me and thought I would be good at it and suggested I give it a try,” McDowall said. “And I was like, ‘No, it’s not for me.’ I had a lot of misconceptions about law enforcement. I thought police and law enforcement were a certain kind of person.”

But he started talking to people in the profession, learned it was mostly about communicating effectively with people, making good decisions, having good character and handling yourself with integrity.

McDowall decided to test the waters by joining the voluntary reserve program where he trained or went on ride-alongs with deputies. Something clicked. He had always found purpose in his previous work, but “it hit a little different,” he said.

“I immediately felt like not only could I do this, but I loved it,” McDowall said. “For the first time in my life I felt like my time was valuable.”

He liked being out on patrol, it was fun and exciting “but it was almost like drinking by firehouse because I was so new at it.” What really hooked him was the classroom study and learning from people who applied what they knew to combat drug addiction.

“And a really close friend of mine had passed away a few months prior from a drug overdose,” McDowall said. “So that really hit with me, how much different work people were doing. It wasn’t just arresting people. It started to seem that law enforcement was more than just what I saw on TV. It wasn’t just high-speed pursuits, kicking doors down and arresting people. It was much more than that.”

McDowall hired on as a corrections deputy in 2006 as a way to get his foot in the door as a patrol deputy. Some of the best patrol deputies start in the jail, learning how to talk with people and building rapport with some of the usual suspects they will meet again on the streets. McDowall planned to spend two years in jail and then transfer to patrol.

But life had other plans. A recession in 2008 and 2009 cut the number of open patrol positions.

“I was frustrated,” McDowall said. “But I decided at that point that I was going to double down and be a jail guy.”

Stark began working in the jail in 2014 after serving eight years in the U.S. Army where he worked as a corrections specialist, a deliberate choice that he could translate into civilian life and a byproduct of his early life with family members who struggled with addiction and crime.

“They had a lot of run-ins with law enforcement,” Stark said. “I grew up in a small town and I saw the negative effect it had on them. I knew that when I got old enough, I wanted a career that was helpful … to do something that would give back to people so maybe they could have positive reactions with law enforcement.”

Stark, who served his first military assignment at Guantanamo Bay Naval Base in Cuba, followed by Iraq and then stateside military prisons, was never interested in arresting people or spending his days on patrol. Communication, building rapport with people, helping them through hard times while inside always felt like a better fit.

“When they come into jail it’s probably their worst day or one of their worst days, so having somebody there that can have a bit of empathy, that understands that everybody that goes to jail isn’t a bad person is important,” Stark said. “And to keep people taken care of if they get agitated or whatever to keep them calm.

“I have my personal experience and know not everybody in my family were bad people,” he added. “But they’d been to jail before.”

Jail time

Corrections officers work from 8 a.m. to 8 p.m. or 8 p.m. to 8 a.m. and every shift begins with a briefing – a rundown of what is happening with the inmates, medical needs, plans for transport, court appearances, reminders to document everything and a word from the chef about what is on the staff menu.

Deputies are not allowed to leave for lunch or dinner, so meals are provided. There is also a state-of-the-art gym they can use during breaks and days off.

Inmates are awakened at 5 a.m. for breakfast. Lunch and dinner are regular meals planned in advance and prepared by inmates who pose less of a safety risk. They can earn time off their sentences by doing everything from food preparation to laundry and janitorial duties.

Those serving time have access to television, radio, medical facilities, messaging kiosks and phones, open-air exercise yards and psychiatric help via closed circuit television because many suffer from mental health issues.

A view of the jail’s red brick exterior accented by narrow windows, gives the impression there are three levels atop a garage. But each of the three floors also have mezzanines in the housing units which are divided into minimum, medium and maximum pods. There is also a segregated area for inmates who pose the highest danger level.

Most cells house a single individual although some have two bunks. A few inmates have been sleeping double the past few months because the jail has been operating at “overpopulation” levels.

“We’ve been steadily in excess of our 127 cap,” McDowall said. “Our absolute cap would be 161 beds.”

The average daily inmate population in 2024 was 124. The average length of stay is about two weeks, but that number is skewed because while some are arrested, booked and released the same day, others may spend a year behind bars.

McDowall credits a “phenomenal pre-trial program” and specialty courts with helping to keep overcrowding in check.

Daily staffing minimums vary. Day shifts require more deputies than nights when inmates are in their cells. There are 31 fulltime budgeted positions for corrections deputies, plus three sergeants and McDowall. The jail is currently down three deputy positions, one of which is frozen because of county budget shortfalls. The other two have received exceptions to be filled. There are also three open nursing positions.

The right stuff

Going to jail as a job, being locked inside a windowless environment to work with people who have been removed from society is not for the faint of heart. But there’s also another side to it, McDowall said.

“One of the things that I quickly learned that kind of blew my mind was that the vast majority of people that come here are actually two different people,” he said.

A high percentage of people are under the influence of drugs or alcohol when they are arrested or arrive in jail, or they are making bad decisions because of addiction.

“And then they come into jail and they get clean, they get sober, they eat healthy and then all of a sudden the person that’s in this jail that doesn’t have access to all those bad choices is a completely different person.”

McDowall says a correction officer learns to wear a lot of hats – mentor, counselor and even father-figure.

“And in some instances, you have to be the stern enforcement because this building doesn’t operate without accountability,” he said.

Recruiting the best candidates to work in the jail also means retaining them. While the pay is on par with other agencies across the state and benefits are good, local housing is expensive and the coastal environment and small-town living is not for everyone or their family. The same goes for working a schedule riven with overtime.

“If you are the kind of person that has to be home every night with the family for dinner, or have weekends off, can’t miss any (kids) games, or have holidays off, all of those things, if those are deal breakers then this is not for you,” McDowall says.

The sheriff’s office looks for people who are flexible, who can celebrate holidays on alternate days, are willing and able — with the support of family — to reschedule vacations if necessary. McDowall seeks people who can sleep days if night shifts are required, who have healthy coping mechanisms so to not take work home with them – inmates can and will hurl insults and pick on flaws.

He looks for recruits who have good structures outside of work, healthy habits and hobbies that help them reset so they can come to work refreshed and ready to be a good teammate.

Stark echoes the importance of work-life balance and added the favorite part of his job these days is hiring people and molding them into the type of deputies the department needs.

“Somebody who has empathy, who isn’t here on a power trip because they want to be in charge of somebody,” he said. “Someone who can learn how to deal with mental health issues, talk to people and make it so that when an inmate goes free they feel like they were not treated badly, that it wasn’t a horrible place and that the staff tried to help them.”

- Garret Jaros covers the communities of Yachats, Waldport, south Lincoln County and natural resources issues and can be reached at GJaros@YachatsNews.com

A challenging job, indeed. May they be blessed with calm, compassionate strength. One more thing~ I enlarged the photo of the meeting in the staff room. What is the significance of the fascinating mural on the wall? Who is the guy on the horse? What is the meaning of the hole in the ground in the mural? Garret, do you know or can you find out? “Inquiring minds want to know”