By GARRET JAROS / Lincoln Chronicle

YACHATS — A young humpback whale stranded for three days on the beach north of Yachats was euthanized shortly after 3 p.m. Monday after efforts to rescue it were unsuccessful.

The whale, which biologists estimated to be 1-2 years old, 23 feet long and 10,000 pounds, washed ashore Saturday afternoon tangled in line from a crab pot. Beachgoers were able to cut the rope free from the whale but it has been trapped in the shallow surf since.

Lisa Ballance, director of the Marine Mammal Institute at Hatfield Marine Science Center in Newport told the Lincoln Chronicle that the effort to free the whale with a pulley system as the tide came in Monday morning failed and that the tentative plan was to sedate and then euthanize the animal. Special veterinarians from Seattle made the decision later in the afternoon.

“A very tragic and sad situation,” Ballance said.

The whale was helpless as experts and onlookers watched as it was buffeted mercilessly by the surf throughout Monday morning.

“The whale is not sedated right now,” said Casey McLean, a veterinarian technician with SR3 Sealife Response Rehab and Research of Seattle, which was called to help.

Members traveled overnight and arrived Sunday afternoon.

“We did provide some sedation last night,” McLean said. “We were going to leave the animal on the beach overnight so we wanted to make the stress was as low as possible. And hopefully just keep the animal calm while it was dry and there was no water.”

Veterinarians and whale biologist did manage to examine the humpback Sunday afternoon before having to retreat from the incoming tide.

“When we drew that first blood work Sunday, we were quite shocked honestly that it was as good as it was considering the animal had already been on the beach for over 24 hours,” McLean said. “And the animal was still responsive. There was no involuntary movement that could indicate some neurologic issues going on.

“So we were pleasantly surprised, which is why the veterinary folks and the biologists that are here agreed that it would be okay to leave one more overnight and try with this tide cycle in the morning,” McLean said.

One last chance

The hope was the whale might have stamina enough to free itself from the shallows itself or with the help of a pulley system rigged by Cascadia Research Collective of Olympia. The group was able to put a releasable harness around the whale that was connected to a line pulled by 30 to 40 volunteers who had rushed to the scene to help.

Cascadia whale biologist John Calambokidis said the main goal of the pulley and rope system was to try to get the whale oriented so that it was aimed out to sea and then preserve any gains as it was hit by the incoming waves, which he said were much bigger at the time.

“And at the key moments the whale actually rolled all the way over and was on its back for a while,” Calambokidis said. “And it became hard to manage those lines and how we’d rigged the harness. Because what we wanted to make sure of is also not having these ropes attached to the whale so we didn’t injure the whale but also so we didn’t entangle the whale.

“What sunk are efforts is as the whale rolled, we could no longer keep the harness positioned properly to both make sure it pulled on the right parts of the body and that we could free it and release it,” he said.

McLean said once the tide is out far enough Monday afternoon she and others would sedate the animal again and draw more blood to reassess.

“But unfortunately, we think the chances are very, very low that this animal would make it through another tide cycle to be able to get back out,” Mclean said. “It’s already been through quite a bit of stress. You may have seen it rolling earlier. There is a lot of concern with that. It’s also been on the beach since Saturday so we are starting to lean more toward the humane thing is to euthanize.”

Mclean added she was glad they were able to try a rescue attempt with the pulley system, something the SR3 team and Cascadia had been successful with in the past.

“We really wanted to give that our best effort,” she said.

When asked about the possibility of the whale’s internal organs being crushed by its own weight while lying on the beach or during rescue efforts, Mclean said that is why the blood is drawn.

“That’s what we’re looking for,” she said. “Our blood analyzer that we can use here on the beach helps us determine how are those kidneys functioning, how is respiration going, what does it looks like inside. It’s not everything you can do inside of a hospital but it is really great to have that on the beach and that really helps us make that assessment.”

She added that the pulley system is not used until the water is deep enough to give the whale a bit of buoyancy “So we’re not tugging on the whale. The line did get a little bit tight at one point but we were keeping a close eye on it. We definitely were not pulling at any strength to actually physically crush the animal.

“And it is important to mention that this really takes a village of people with different expertise,” Mclean added. “So there’s a lot of folks here with a lot of different knowledge so we can make sure we’re all watching for different things.”

Growing numbers

Gray whales that migrant north and south along the Oregon coast are the most abundant with a population three times as large as two populations of humpbacks that also journey from feeding waters off Alaska to breeding and calving areas off the coasts of Mexico and Central America.

NOAA Fisheries says that before a final moratorium on commercial whaling in 1985, all populations of humpback whales were greatly reduced, most by more than 95 percent. The most recent reports from NOAA say the species is increasing but face threats from entanglement in fishing gear, vessel strikes, vessel-based harassment, and underwater noise.

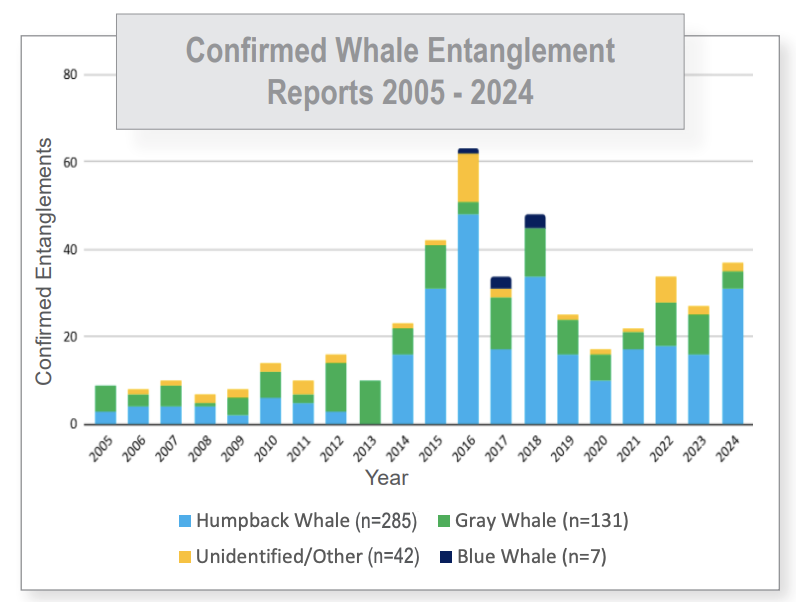

But because of their migration pattern which is changing due to climate change, NOAA Fisheries said it has responded to an increasing number of entanglements reported to the West Coast Marine Mammal Stranding Network.

In 2015, a total of 50 whales were confirmed entangled off the coasts of California, Oregon, and Washington – the highest since record keeping started in 1982.

But that dropped to a total of 36 in 2024, according to NOAA, with 31 of those being humpback whales and just four gray whales. There were three humpback entanglements in Oregon in 2024; California had by far the most with 21 entanglements.

NOAA’s 2024 report said responders were able to successfully remove gear from three entangled humpback whales and in 12 cases no gear was removed.

Cascadia info

Cascadia primarily studies and monitors the abundance of humpback, gray and blue whales up and down the West Coast, Calambokidis, said. It also has a stranding response.

“All our data shows humpbacks are increasing in numbers at about eight percent per year,” Calambokidis said. The California-Oregon population when I started studying it in the mid-1980s we estimated at 500. We’re now at over 7,000.”

Where the North Pacific population of humpbacks travel to and from – feeding in colder water and then traveling thousands of miles to breed and give birth in warmer water – varies among different herds along the West Coast.

“It actually shifts as you go up and down the coast,” Calambokidis said. “But on this part of the coast a slight majority travel to Mexico, some to Central America and some to Hawaii.”

Those traveling to Central America tend to come from southern California, then as you go north – more to Mexico and Hawaii, he said. By the Washington border it is about half and half. Humpbacks who feed in southeast Alaska migrate almost entirely to Hawaii.

“They are actually pretty loyal to certain feeding areas and breeding areas.”

- Garret Jaros covers the communities of Yachats, Waldport, south Lincoln County and natural resources issues and can be reached at GJaros@YachatsNews.com