By FEDOR ZARKIN/The Oregonian/OregonLive

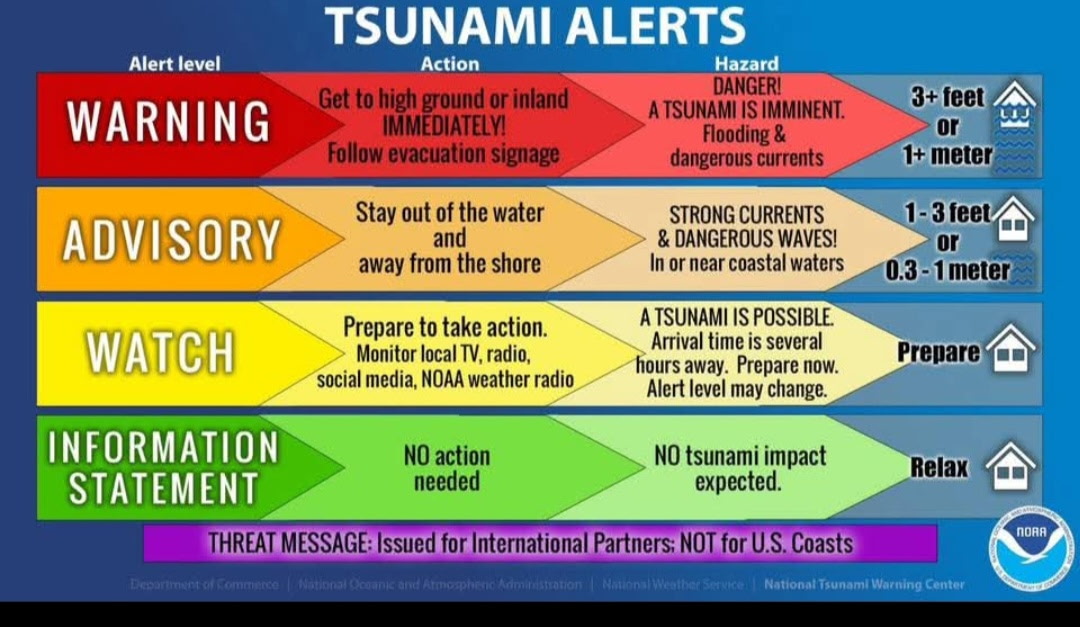

Tsunami warnings for residents and visitors to the Oregon coast will not be affected — for now — after an Alaska earthquake center decided to backfill federal cuts to an alert system that provides swift and accurate alerts.

Sen. Maria Cantwell, D-Wash. this month urged federal officials to reinstate a $300,000 annual grant to the Alaska Earthquake Center in Fairbanks, which runs 250 seismic stations across Alaska. The stations are part of an alert system that also informs Oregonians about the strength and timeline of a potential tsunami, giving people critical information to find safety.

The Alaska Earthquake Center said it was going to stop supplying data to the Tsunami Warning Centers because of the budget cuts, which would have meant less accurate and less timely notifications about tsunamis from the federal centers.

“Seconds matter during a tsunami, and coastal communities can have as little as 20 minutes to evacuate and prepare for an incoming wave,” Cantwell wrote in a letter to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s administrator Nov. 19. “Any delay in the data could erode critical time to get people out of harm’s way.”

Tsunamis and earthquakes are a near-constant concern along the Pacific rim, one of the most seismically active areas on the planet. Just this year, a record-breaking earthquake near Russia triggered concerns about a tsunami that ultimately did not materialize. Nearly 20,000 people died in 2011 as a result of a tsunami triggered by the Great Tohoku earthquake near Japan, and crashing waves reached Oregon, causing damage but sparing lives.

The NOAA grant paid for maintenance of nine particularly important and hard-to-reach stations and for the data from the Alaska Earthquake Center’s stations to be instantly relayed to the federal warning centers.

Now, the center has decided to pay for the data to go straight to the warning centers out of its own budget, spokesperson Elisabeth Nadin said in a text message. But the center won’t pay for the maintenance of the nine seismic stations that the federal government had previously paid for. Those are in very remote parts of the state and are “extremely expensive” to get to, Nadin said.

Those nine stations also happen to be particularly important, said University of Washington seismologist Harold Tobin, because they are in areas that are particularly seismologically active.

“It’s certainly one of the most remote areas that exist. But it also is a place where there’s a lot of earthquakes and a lot of underwater earthquakes,” Tobin said. “It is a region that it’s absurd to not be monitoring closely from the perspective of tsunami warnings.”

The nine stations will keep sending data until they stop working due to a natural event or a malfunction, Nadin said.

The Alaska Earthquake Center’s funding was cut in fiscal year 2024, NOAA spokesperson Kim Doster said in the statement, but the center has continued to provide the agency with real-time data nonetheless.

Doster said in a written statement that the agency does not rely on any single source of information for its alerts, adding that the Alaska Earthquake Center at the University of Alaska is “one of many partners” providing information.