By DANA TIMS/Lincoln Chronicle

A California brown pelican glided past Yachats earlier this month, which is not all that unusual. But it, and a bird rescue group in California, had an amazing tale to tell.

But no one would have known a thing about the pelican’s travels if not for a new, specially equipped antenna at the Cape Perpetua Visitors Center that is now broadcasting the movement of birds and other species that have tracking tags attached by researchers.

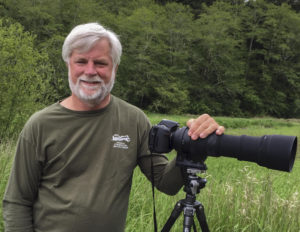

“We are already learning so much,” said Roy Lowe of Waldport, a retired U.S. Fish and Wildlife official and avid wildlife photographer who helped both with the antenna’s installation. “What’s particularly amazing is that all of this has us asking almost as many questions as we’re answering.”

Tracking data recorded by the formally named Motus Wildlife Tracking System indicated that the adult male pelican cruising past Yachats was incapacitated more than a year ago in Santa Cruz, Calif., when injuries from a fishing hook and line seriously affected his legs, wings, keel and hocks.

The wounds required a 45-minute surgery in May 2024 at International Bird and Native Animal Rescue. Following a lengthy rehabilitation and tagging, the pelican was released into San Francisco Bay on July 19, 2024, after what researchers described as “a good drink and some stretching.”

Aside from a few visual sightings and a ping from a Motus tower in Mexico, the pelican’s whereabouts have been something of a mystery. Until now, that is, when he was in contact last Thursday for about five minutes with the Cape Perpetua antenna – one of six on the Oregon coast and among the more than 2,000 stations now operating around the world.

“This is such a benefit for bird researchers everywhere,” Lowe told Capital Chronicle. “And I really believe that we are only scratching the surface.”

Long-held assumptions about a particular bird’s migration route, for instance, have been completely upended. In other instances, the real-time information broadcast from tagged birds back to Motus towers have recorded incredible speeds for birds flying high enough to get caught up in stormy torrents.

“To say the least,” Lowe added, “all of this has been incredibly eye-opening.”

A vast network

Motus, which means ‘movement’ in Latin, is led by Birds Canada, an Ontario-based bird conservation organization. The system, whose origins date to 2010, uses information from tiny radio transmitters to track wildlife on the same frequency across the globe.

Results produced so far are impressive.

A total of 57,218 animals representing 455 species have been tagged with either battery-powered or solar-powered transmitters. The network’s 2,197 stations operate in 34 different countries and have contributed to research featured in more than 250 publications.

“Motus has really revolutionized how we undertake research on migratory animals,” Stuart Mackenzie, Birds Canada’s director of migration ecology, told the Lincoln Chronicle. “The data we have developed so far are quite remarkable.”

Mackenzie said his organization serves as the network’s central data hub, but that it is heavily reliant regional partners to make the whole thing tick.

“The real novel aspect is the collaborative nature of the system,” he said. “For the first time, someone can tag a bird in Nova Scotia and follow, in real time, as that bird migrates to Mexico. It’s really extraordinary.”

During a recent telephone interview, Mackenzie used his computer to check in on the results of the new Cape Perpetua tower, which is under the auspices of the U.S. Forest Service and went up in late April immediately adjacent to the visitors’ center.

A total of 10 tagged birds have flown close enough during that time – about 10 miles – to show up on the west-facing antenna’s data report. Those include seven dunlins, one short-billed dowitcher and two brown pelicans.

The pelican, Lowe added later, is the first instance of a Motus-tagged brown pelican detected north of Tomales Bay, Calif. And of the 10 birds recorded by the Cape Perpetua tower, four, all dunlins, were also detected by the east-facing Motus tower at the Hatfield Marine Science Center in Newport.

“You can look up any site,” Mackenzie said, “and see migration stories that can be told from local, regional and even hemispheric viewpoints.”

An immediate hit

At Cape Perpetua, a kiosk will be added in the near future to help the nearly 400 visitors a day who show up there better understand the power and reach of the tower, said Reba Ortiz, Cape Perpetua Scenic Area’s supervisor.

Ortiz said she was initially concerned that trees in the area, along with the geographical nature of the cape itself, might inhibit the antenna’s reach. Thankfully, she said, that has not been the case.

“The antenna is right next to our front deck, where there’s a nice little pocket of ocean view,” she said. “And it’s already turning up some awesome connections between different ecosystems and migrating species.”

She is also anticipating that future detections will include bats and even certain tagged insects.

“Birds also seem to be our first step, but there will be other animals we’ll be able to track, as well,” Ortiz said. “The whole goal is to use this as an educational opportunity to inform the public about the cool scientific things taking place right outside our front door.”

Fast and furious

Lowe, meanwhile, checks the Motus site regularly to keep current with the latest detections. But already, he said, information from the Cape Perpetua tower, and others, is upending some long-held notions about flight behaviors.

One tagged species, for instance, has long been known to migrate between Canada and Mexico, so a simple trip down the West Coast seemed to most obvious. As Lowe and others looked at data collected at various towers, however, it became clear that something else entirely was happening.

“I checked and saw that some of these birds were turning inland and detected next in Wisconsin, then the Florida panhandle and on to Colombia,” he said. “It just completely blew my mind.”

In another instance, Lowe saw tower information indicating that a dunlin flying between a tower at Langlois in Curry County was able to reach Cannon Beach in only 90 minutes. A simple mileage calculation indicated that the bird, evidently flying high up and aided by extremely strong winds, had reached a top speed of 70 mph.

“The amazing thing is that all of this information is both public and available on anyone’s computer,” he said. “Birds from anywhere in the world are suddenly right at our fingertips.”

- Dana Tims is an Oregon freelance writer who contributes regularly to Lincoln Chronicle and can be reached at DanaTims24@gmail.com

Excellent storytelling.